The looming debt-driven recession

The rapid increase in corporate and government debts since the last great recession to levels unseen before is an alarming sign for the future of the world economy. High debt levels coupled with increasing interest rates, an up-tick in inflation, and trade wars represent an explosive mix that can put the U.S. and the world economy at a risk of a serious recession during 2019. In a world loaded with debt, the biggest enemy becomes higher interest rates.

Unprecedented levels of corporate debts

Contrary to the previous great recession of 2008, which was mostly driven by consumer debt, the current debts are primary carried by corporations and governments.

Large corporations across the globe, and even more so in the U.S., have been accumulating debt at a rapid pace since the last recession. When calculated as a percentage of GDP, the total debt of America’s non-financial corporations reached 73.3% in the second quarter of 2017. This is a record high.

On the face of it, this is surprising considering that these same corporations have benefited from high profit during the same period. In fact large corporations – especially the largest one in the high tech industry – have been hoarding hundreds of billions of dollars in cash. Hence the decision to increase the debt was not driven by companies’ inability to self-finance their investments, but rather by their desire to increase corporate debt leverage (money is easy and cheap). To a large extent, corporations have used their improved profitability not to invest, but to leverage it and go deeper into debt. So, what did corporation do with the money, where did it all go?

To shareholders through stock buyback and dividends.

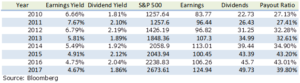

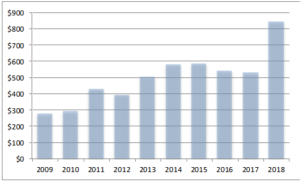

According to JP Morgan, the S&P 500 will buy back a record $800 billion of their own shares in 2018. That is an increase of almost $300 billion dollars over the previous year, which was already one of highest ever recorded (See figure below.) In addition, corporations have been increasingly paying out dividends to their shareholders. Payout ratio in 2016-2017 reached over 40%, 13 percentage points higher than in 2010.

To mergers and acquisitions

Mergers and acquisitions announced the first two months of 2018 are worth $1.1trn, according to Dealogic. This is 42% more than the value of deals made in the first three months of 2017 and is set to be the strongest first-quarter result on record. This follows very strong 2015 through 2017 M&A activity, where deals were worth around $4trn each year – this compared with $2trn to $2.5trn worth of M&A deals in 2009-2010. Interesting fact: 2018 M&A level is close to that experienced in 2007 just before the great recession.

Source: J.P Morgan U.S. Equity and Quantitative Research, Bloomberg (in billions)

This increased level of debt was, as expected, met with higher degree of riskiness; increasing the likelihood of large scale corporate debt default. Currently, according to S&P Global, the worldwide average corporate credit rating stands at BBB- down from BBB since the last recession. Obviously, this global average hides a wide range of corporate risk. Default, to become dangerous, needs only to reach a few corporations to trigger an uncontrollable sequence of events: defaults lead to higher interest rates that lead to more defaults… How will corporate defaults impact financial institutions? Will they represent systemic risks as those of the last great recession? Contrary to the debt crisis of 2008, where sub-prime and other real estate related loans were nebulous, corporate debt is more defined and its risks have clearer demarcation points. Hence they represent less of a systematic risk to financial institutions that issued them.

The global government debt and the impending U.S. government debt bomb

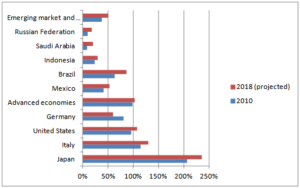

Governments have also drastically increased their debt. Currently, government-issued debts stand at over $87trn globally. In the early years after the great recession, more debt was necessary to alleviate the crisis consequences and restart the global economy. However, as the years have passed and economies recovered, debt levels continued to increase although at a slower pace – in the developed economies as well as in the emerging markets. According to the IMF, global gross public debt has risen in recent years and is projected to reach 82% of GDP in 2018. Japan has the highest debt levels in the world with 236% of GDP this year. Even Saudi Arabia has seen its government debt level skyrocket in recent years due to lower oil. In lower income economies debt is projected to reach 46% of the GDP, a 14-percentage-point increase since 2013. Rich economies public debt has been about 105% of GDP on average since 2012, a level not seen since World War II.

Source: IMF

And yet this does not take into account the expected U.S. debt surge resulting from the tax cuts and spending increase recently passed. With tax cuts and increased federal spending, the positive effects usually and naturally come first, before their negatives as the bill comes due later. 2018 will benefit from the positive affect. However, as 2019 begins and the amount of the bill due becomes clearer, the negatives will overcome the positive. Although, contrary to corporations, U.S. government cannot technically default on its debt since U.S. debt is issued exclusively in U.S. dollars (although it can default politically as Congress may block debt ceiling increase or refuse the budget appropriation). The higher debt will result in higher interest rates (it already began.) This will increase corporate defaults risk and reduce consumer spending. Refinancing the corporate debt, as it comes due, will become significantly more expensive as interest rates increase, since most of the debt was contracted during the low interest rate period. In addition, higher rates will hamper consumer spending, thus negatively impacting corporate profits and the general economy. The timing of the occurrence of these two events – higher interest rates and reduction in consumer spending — could represent a double whammy for corporations, thus accelerating corporate defaults.

Although the U.S. and other advanced economies have the luxury to issue debts in their local respective currencies, the same cannot be said about other countries that are forced to borrow in “hard” currencies. These countries have also increased their debts levels over the last decade and will feel the burden of higher interest rates the most. Some may be forced to default on their debt (Argentina is already experiencing difficulties, Turkey could be next.)

The up-ticking inflation

According to the IMF, the worldwide inflation rate is projected to reach 3.5% in 2018 up from 3% in 2017 and 2.8% in 2016. For the U.S. the increase is even more pronounced. Inflation went from 1.3% in 2016 to 2.5% in 2018. This may not seem high by historic standards. However, any resulting increase in the interest rate of 1 percentage point can lead to an added burden of up to $717 billion for governments and up to $585 billion for corporations. The accelerating inflation is primarily driven by the structural tightening of the labor market – which represents a long-term trend, and to a lesser degree by the recent increase in energy prices.

The global labor market is tightening. The opening of China, and to lesser extent India, in the last 25 years have brought a never-before-seen influx of labor (mostly low-cost labor) to the global market. This has kept global production cost in check and inflation lower. However, the labor market is tightening in China as its population is getting older. The same is true in Europe and the U.S. and across most of Asia. Furthermore, increased nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiment across the western world is limiting the influx of the needed foreign labor to these economies.

Oil price has doubled in the last 12 months and is currently consistently trading above $70 per barrel. The withdrawal of the U.S. from the Iran deal, which puts at risk Iran’s oil exports, the collapse of the Venezuelan oil production, and the security issues impacting Libyan oil exports have significantly tightened global oil supplies. Higher oil and energy prices have historically resulted in higher inflation across the economy.

The U.S. initiated trade wars: the match that will ignite the powder keg?

The current state of affairs of the world economy does not need the added and unnecessary risk of trade wars initiated by the current U.S. administration. To make matters worse, these policies do not seem to have clearly defined objectives and strategy. They seem more improvised than thought through.

Freer (if not free) trade has been the bed rock of capitalism – in theory as in practice — from the invisible hand of Smith to the comparative advantage of Ricardo, to the establishment at the initiative of the U.S. of global institutions boosting freer trade. The false basic motivation behind the current trade wars initiated by the current American administration is that trade deficits are bad for the country experiencing them.

The concept of “Made in” is obsolete. Nothing, or almost nothing, today is entirely made in a single country. It may be assembled in one, but from parts made in many others. Today, each iPhone — an American product par excellence — sold in the U.S., contributes to the trade deficit with China. However, iPhones sold in China do nothing to reduce the deficit. Furthermore, physical products account for less in the global economy than do services and intellectual property. Focusing on trade deficits is misplaced. The real focus should be on intellectual property protection.

The increased tariffs on imported goods will directly impact inflation, since imported goods will become more expensive and alternative locally made products are not readily available. This unnecessary added inflationary pressure will dramatically increase the risks of higher interest rates – public enemy number one for today’s world economy.

So, now what?

Various types of debts have reached unprecedented levels, fueled by historically easy and cheap money over the last decade. Interest rates are going up and most likely at an accelerating pace moving forward. The two deliberate and unnecessary U.S. policies –deficit spending and tax cuts, and trade wars — will make this situation explosive because of their effect on inflation and interest rates. These policies were unnecessary, because the U.S. economy did not need the stimulus resulting from spending increase (it needed the opposite), and the trade wars seem more driven by politics than economics. These two policies will result in higher interest rates than what they would normally have been. Brace yourself for a rocky 2019!

Recent Comments